Overview

Field research involves engaging with a diverse array of people, practices, objects, and ideas that together shape the dynamics of a site. Recognizing how these different actors—human and non-human—contribute to the making of a field is crucial for understanding how knowledge, power, and meaning circulate within it. Actor-Network Theory (ANT) draws attention to this complexity by encouraging researchers to consider the agency of all entities involved in field formation, including technologies, documents, infrastructures, and environments. Rather than treating the field as a preexisting backdrop, ANT highlights how it is actively assembled through networks of relations among these heterogeneous actors.

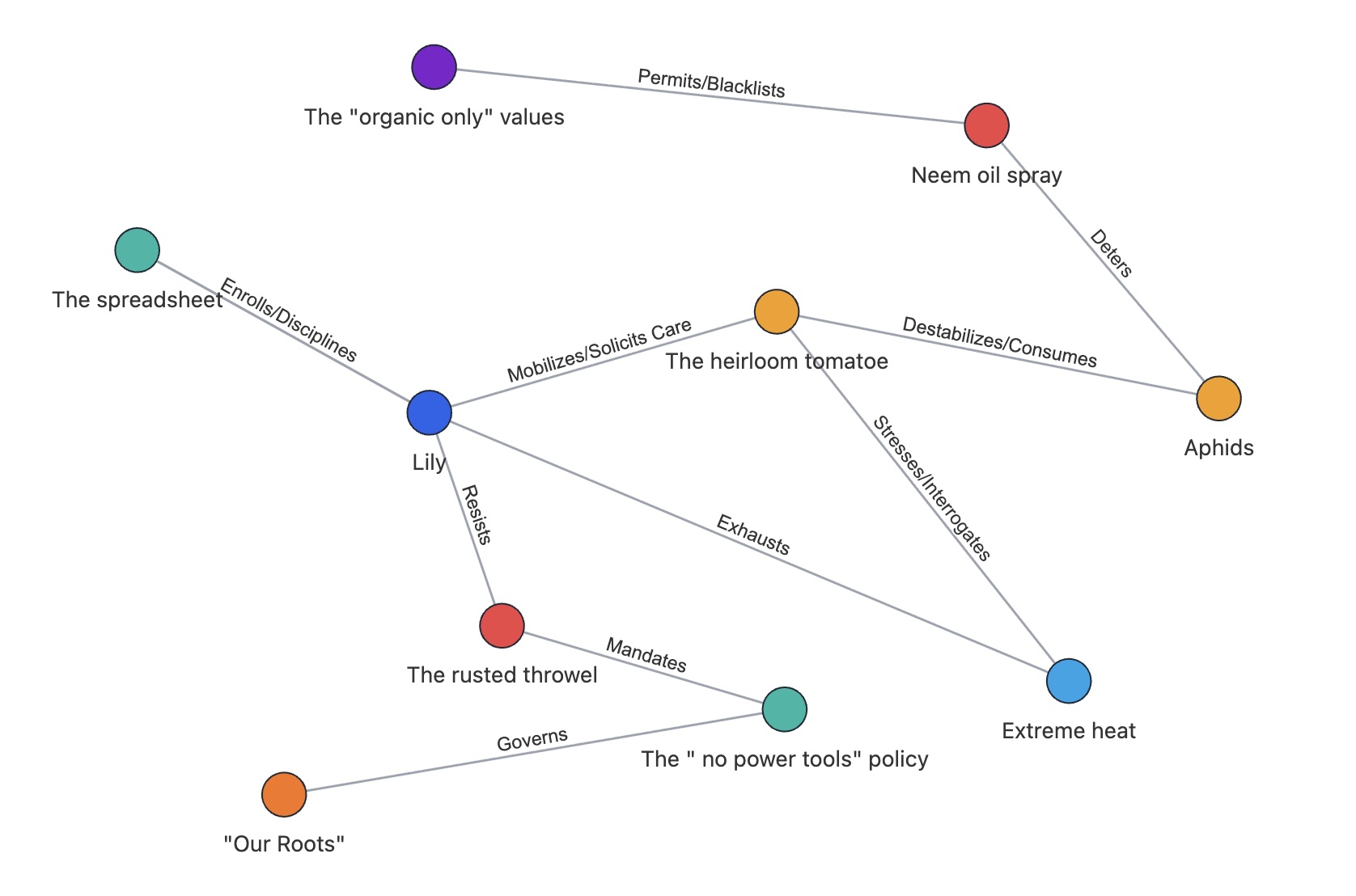

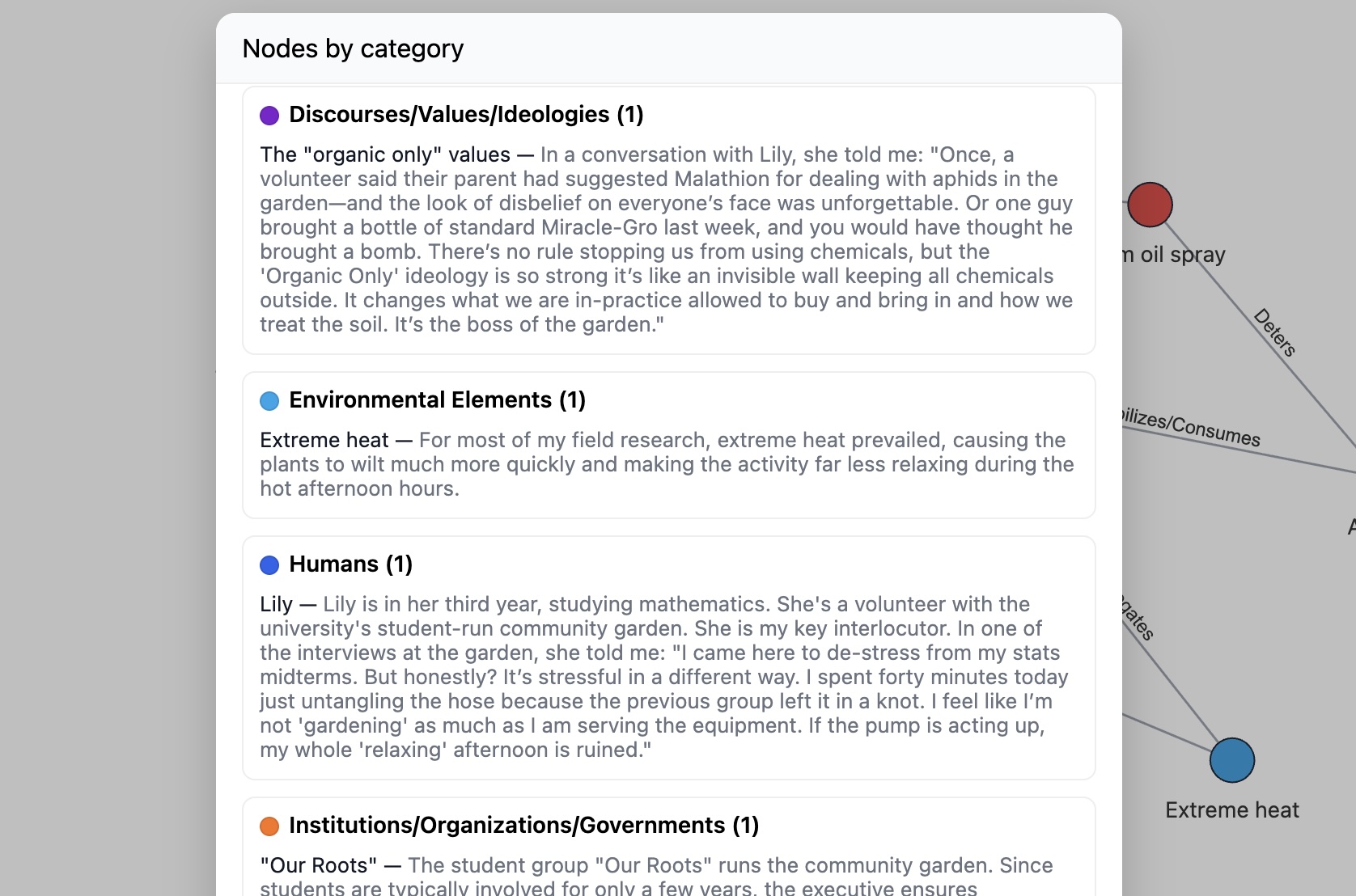

The interactive network mindmap tool provides a way to visualize and engage with this relational complexity. Designed for ethnographers and other field researchers, it allows users to map, categorize, and connect the various entities that constitute their fieldsite—people, policies, technologies, environments, and more. By making these relationships visible, the tool helps identify overlooked connections and dependencies, supporting a more reflexive understanding of how the field operates as a networked system. Through its visual and interactive interface, it translates the principles of ANT into a practical method for exploring how research contexts are co-constructed by diverse human and non-human participants

An example of the tool in use

The following analysis illustrates how FieldWeaver can be used to analyze and visualize ethnographic fieldwork in a university community garden. To view and interact with the network map, please download this file containign the nodes, connections, and descriptions, open FieldWeaver, click Load JSON, and select the file you downloaded. The map should then open. Below are a few screenshots illustrating what you will see.

The Distributed Gardener: An ethnographic analysis of the campus community garden

My initial ethnographic research question focused on how student volunteers—members of Our Roots,” a student group “— manage their community garden plots on my university campus. However, attending closely to actors beyond those named as ‘student-volunteers’ in my fieldnotes quickly revealed that the work was not simply carried out by volunteers themselves. Rather, their actions were continuously shaped through pushes and pulls exerted by a heterogeneous web of many demanding actors.

I spent many afternoons and evenings during the spring and summer conducting participant-observation alongside volunteers, particularly Lily, a third-year student majoring in mathematics. I took extensive fieldnotes and conducted a series of interviews. I additionally used network mapping as both an analytical and representational method to trace relations among human and nonhuman actors identified through interviews and field observations. Rather than locating agency solely in individual actors, the map makes visible how action emerges through connections among volunteers, documents, policies, tools, organisms, and environmental forces. By foregrounding relations such as enrolment, delegation, constraint, and antiprogramming, the network enables an analysis of how work, care, and exhaustion are produced across the assemblage, rather than attributing outcomes to intention or motivation alone. Instead of beginning from human actors and their motivations, the map therefore traces how outcomes are not controlled by a single actor.

For instance, one of the key nonhuman mediators in this assemblage is the watering roster/spreadsheet, which operates not as a passive record of who waters the plants and when but as an actor that disciplines time and labor. By ensuring that students show up and perform labor according to the collective schedule, the spreadsheet translates a diffuse commitment to volunteering into a structured obligation. The presence of unassigned time slots further urges volunteers to stay/work more than what they committed, extending labor beyond explicit agreement. Here, care is not simply offered; it is produced through inscription. The spreadsheet thus enrolls humans into a temporal order that stabilizes participation without requiring direct supervision.

Governance in the garden is similarly delegated to policies and tools. “Our Roots,” as the student organization that runs the garden, governs indirectly through the ‘no power tools’ policy. While it excludes power tools, this policy is materially enforced by inclusion of basic tools including a rusted trowel that Lily particularly dislikes and whose resistance fights Lily’s muscles. As such, the trowel functions as a delegated enforcer of policy: it translates an abstract rule into bodily strain. What appears as individual effort is in fact an effect of policy enacted through material mediation.

Biological actors also play a central role in mobilizing action. The heirloom tomato solicits care through visible stress, “calling” for water as its leaves wilt. This call is intensified by extreme heat, which accelerates wilting while simultaneously “exhausting” the bodies enlisted to respond. Heat thus acts as a nonhuman mediator that destabilizes the assemblage on multiple fronts: it increases the frequency of care demands while reducing the capacity to meet them. Care, in this configuration, becomes temporally compressed and energetically costly.

The tomato’s vulnerability is further destabilized by aphids, which function as an antiprogram—an actor whose actions interfere with the stabilization of the garden assemblage by consuming plant matter and undermining growth. The response to aphids is constrained by the ‘organic only’ values, which operate as a normative filter, permitting some interventions while blacklisting others (such as Malathion). The collective values in the garden actively reshape the field of possible action.

Within these constraints, neem oil is enrolled as a compromise actor. It deters aphids but does not eliminate them entirely. It therefore produces a partial and ongoing intervention rather than resolution. The persistence of aphids is not a failure of action but an effect of value-laden translation: effectiveness is deliberately traded for ethical alignment. As a result, the assemblage remains in a state of continual adjustment rather than closure.

What the network makes visible, then, is not a hierarchy of control but a series of unstable translations through which care is enacted. Documents produce labor, policies harden into tools, plants mobilize attention, pests disrupt order, values constrain efficacy, and heat reconfigures endurance. Exhaustion emerges not as a personal condition but as a distributed outcome of the assemblage itself. The garden is thus not sustained by individual intention alone. It is held together—precariously—through the alignment of heterogeneous actors whose interests never fully coincide. The map thus tells a story of care as an ongoing achievement: contingent, mediated, and continuously at risk of unraveling.